Family trees es una serie de dibujo y montajes a muro que exploran relaciones entre un lugar y formas de memoria. El dibujo esta basado en muestras de diferentes especies de árboles resguardados en archivos botánicos, en donde los cortes transversales de la madera provocan que la geometría radial del anillo del árbol pase a verse más ‘líquida’, sugiriendo formaciones que asemejan vistas topográficas o el ‘escurrimiento’ de su propio registro del tiempo y el entorno. El dibujo calado sobre madera genera huecos a través de los cuales se entreven imágenes de fondo -registros fotográficos o materiales específicos de los lugares-, buscando contraponer lecturas entre sitio, historia y vidas más extensas que la humana que permitan cruzar y conectar generaciones.

Con el apoyo en investigación de la Dra. Alejandra Quintanar, coordinadora del Laboratorio de Tecnología de la Madera de la UAM Xochimilco, de la Xiloteca de la UAM y del Instituto de Biología de la UNAM.

XV BIENAL FEMSA

Museo Regional de Guanajuato Alhondiga de Granaditas, Guanajuato, MX

2024

Dirección artística por Mariana Munguía

Curaduría por Pamela Desjardins y Christian Gómez

Curaduría de sitio Isis Yepez

Curaduría asociada Eugenia Braniff

Texto por Pamela Desjardins

Bajo el entendimiento del paisaje y la tierra como archivo, este proyecto apela a la memoria que guardan los materiales y los lugares por sí mismos, así como a las huellas que quedan en ellos al habitarlos y manipularlos. En su conjunto, las piezas retoman la historia del recinto de la Alhóndiga –originalmente concebido para el almacenamiento de semillas– que hoy resguarda objetos de la región, como la alfarería chupícuara. Las arcillas utilizadas por la cultura chupícuara provienen de diversas zonas del estado de Guanajuato, al igual que las que cubren los muros de la sala, las cuales fueron recolectadas por la artista en colaboración con investigadores del Laboratorio Nacional de Ciencias para la investigación y Conservación del Patrimonio Cultural (LANCIC). Al fondo, el mural de madera basado en anillos de árboles del Bajío, como el cedro blanco, el oyamel, el naranjillo, el ciruelo, el encino y el capulincillo, así como la escultura de un tronco en putrefacción, aluden al paso del tiempo y a los ciclos de la vida.

Árboles genealógicos (Bajio)

2024

Dibujo calado sobre madera (frente) y arcillas de Chupícuaro, Acámbaro, Puruaguita, San José Rincón, Las Tinajas, Cerro del Toro, Jerécuaro, La Purísima, Tarandacuao, Cañitas, Dolores, San Anton de las Minas, Santa Rosa de Lima, Los Mexicanos, y Valenciana, (fondo)

360x360cm (frente) 366x378cm (fondo)

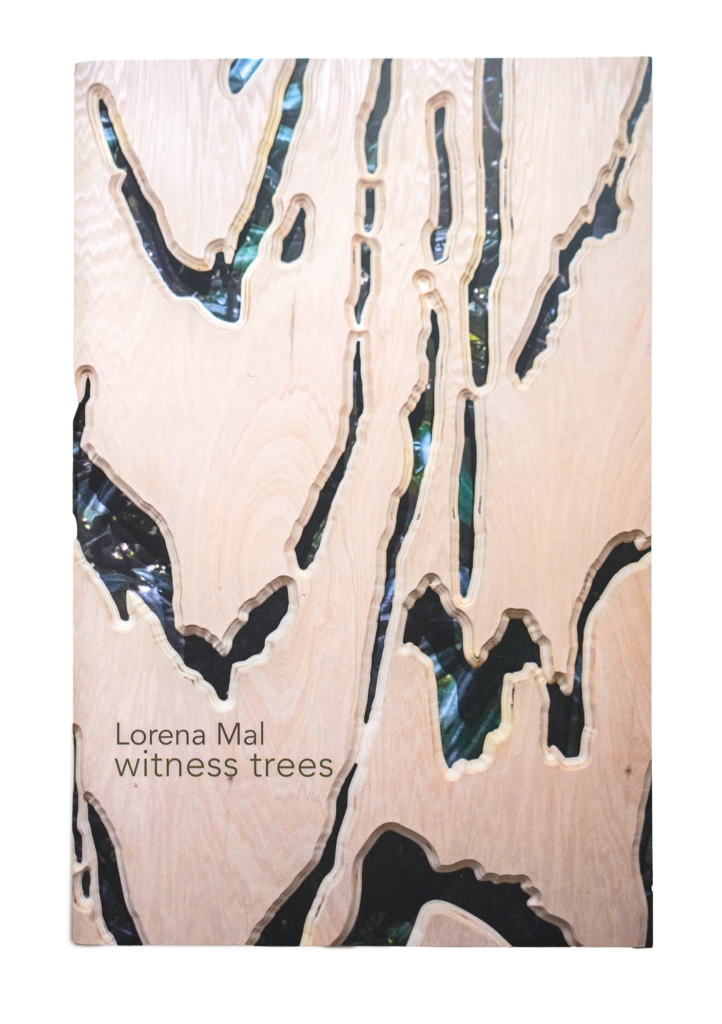

Witness Trees

Smith Gallery, Davidson NC, EUA

2022

Curated by Lia Newman

Text by Violeta Burckhardt

The exhibition Witness trees is part of the evolutionary process of Lorena Mal’s explorations of landscape as common ground—a way of bringing diverse people, places, and time scales together. This grounding, site-specific approach understands nature as a cultural construct and the territorial boundaries that define it as an ungraspable threshold in the face of deep time. It recognizes landscape as a perspective through which geopolitical manifestations of space can be reconfigured—a modality for the reinterpretation of history based on the selection, or subtraction, of information through a collective process. By focusing on the wandering history of the Magnolia grandiflora as her subject, the artist weaves human and non-human survival stories through the voices of plants and the ecologies that have resulted from their displacement. By reimagining trees as subjects, Mal develops new tools to understand preservation as a radical form of transformation that understands nature as a decentralized and non-anthropocentric concept.

As we enter the gallery space, we feel the weight of the soft but sharp ochre color emanating from the walls behind us, forcing us to look back. The natural clay hue locks our senses —a small gesture toward recognizing the importance of history in constructing the present. The color was extracted from Cecil soil, a mixture of clay, sand, and ferric oxide found across the Magnolia grandiflora ’s North American territory and habitat, and in particular, in Davidson, North Carolina, where the exhibition takes place. Born out of the weathering or oxidation of pigment, the ochre color on the walls captures life as a chemical process, linking it to our bodies through the oxygen that we also carry within our flesh.

Before us lies a book. Psalmodia Naturalis (in xóchitl, in cuícatl), 2020-2022, rests open on top of a pedestal made from rammed earth, a mixture of local Cecil, as well as Mexican soil brought by Mal from her own home. By mixing the two soils, Mal strengthens the structure of the foundation, while acknowledging the ground as common. As an architectural and vernacular technique found across the globe, rammed earth functions as a symbol of sustainable building practices and embodied energy in mineral form. Few Cecil soils that we now encounter can be found in a virgin state. Earth, like the biotic and abiotic elements that compose it, is part of a complex and shifting mixture of land and a direct result of a mosaic and cultivated culture.

Spread between the pages of Mal’s book, Psalmodia Naturalis (in xóchitl, in cuícatl)’s, pressed magnolia flowers surface from side to side. This majestic evergreen tree, growing over 30 meters tall, has become a ubiquitous component of gardens across a range of geographies worldwide. Though commonly regarded as native to the North American continent, its roots run deep, within a network that now extends its origin. Fossil records show that magnolias once grew in the wild as far away as Asia 100 million years ago, yet the oldest western recording is found in mesoamerican history, through illustrations of the now extremely rare Magnolia dealbata en el Códice De la Cruz-Badiano o Libellus de Medicualibus Indoorum Herbis. With Mal’s new work Psalmodia Naturalis (in xóchitl, in cuícatl), Mal uses a historical archive, the Psalmodia Christiana (1558–1583), where the magnolia was first recorded, as a way of unearthing pre-colonial narratives of place. Brought to life as a way of bridging ancestral and colonialist visions of landscape, this book marks an important turning point in Mexican history—the moment when tradition was able to survive through the entanglement of different perspectives, images, and language forms. This combination of meaning and cultural systems, also known as syncretism, allowed pre-Hispanic tradition to survive in composite form.

Psalmodia Christiana, no longer found in its place of origin, has a migration history of its own. Now, privately owned and located in the John Carter Brown Library in Providence, Rhode Island, the Psalmodia Christiana is part of a growing archive of rare books, manuscripts, and illustrations that mark the history of exploration and colonization of the “New World.” Now fully digitalized and accessible online, the contents of the library are part of an interconnected community where knowledge, though locally conceived, is given the chance to live a second life through the evolution of a society that understands itself as a planetary whole. As Mal delves into the content of this book of psalms, a new landscape unravels as certain species of plants surface, page after page—as relics of a live but hidden past. Through language, rhythm, and repetition, Mal paints a new image of landscape as a space for critical reflection and polyphonic lyre.

Mal uses botany as a geopolitical narrative device to link indigenous thought with western scientific tradition. Written within the premises of the colonial convent of Tlatelolco, the long-forgotten Psalmodia Christiana, originally envisioned as a book of psalms, is transformed by the artist through a process of exhumation. By reproducing her own version of this text, Mal excavates new narratives through omission, a technique that characterizes a larger body of work, and a common denominator in her research. Like reverse archeology, the artist constructs a new image by acknowledging the potential of withdrawal as a tool for emergence. The book, a map of sorts, describes the territory through a cosmology of mixture and an example of the potential of hybrid forms of history and storytelling as a way of being in and with the world. Psalmodia Naturalis is an act of preservation through transmutation that understands landscape as a universal and timeless language.

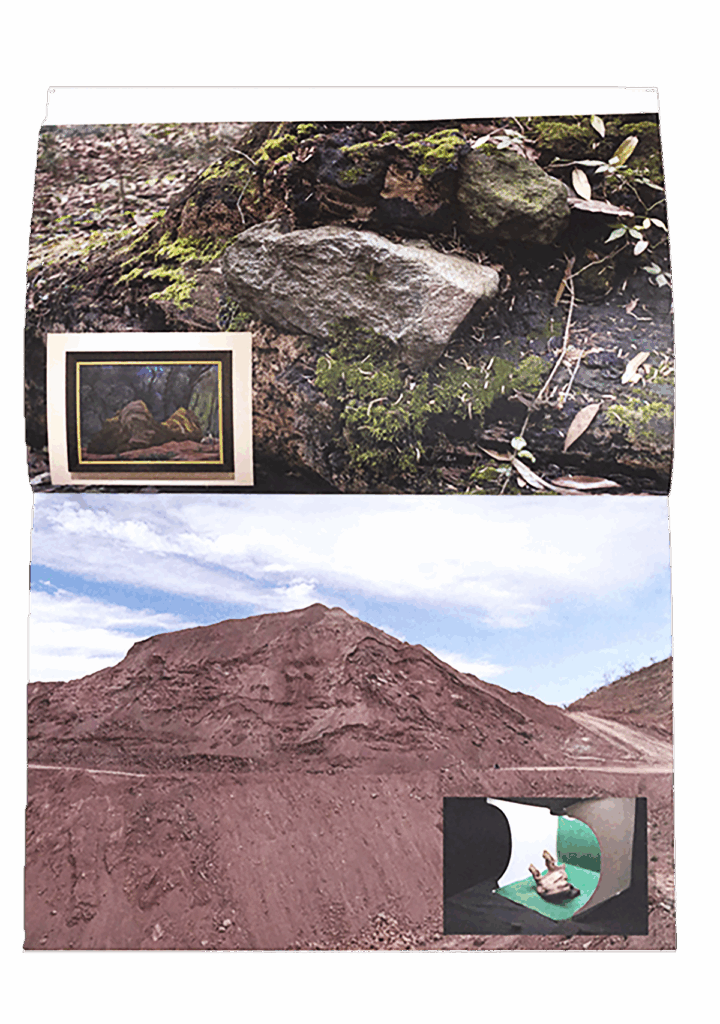

Mal’s Family Trees (America: Magnolia) consist of a series of tree ring images carved directly on top of and into red oak wood panels. The lines, based on samples included in the American Woods Archive by Romeyn Beck Hough (1857-1921), offer a dendrochronological display of the life of Magnolias, creating a topography of their own. Similar to a map, these lines follow a path of infinite repetition. These patterns contextualize the timeline hidden behind its veil as a symbol of life and continuity. Almost invisible, Mal’s large-scale photographs act as a backdrop to these carved tree ring surfaces. One image is that of a tree found in the garden of her close friend Felipe in Mexico—a tree that his family has taken care of for generations and under which lie the ashes of his grandparents. The second image depicts another magnolia tree from the nearby Latta Plantation Nature Preserve and former slave plantation. Both images epitomize archives of the past, living markers that link territories through montage.

Witness Trees understands history as fluid and considers song and breath as not limited to humans—a metaphysical element through which the world communicates back to us. The magnolia’s pressed leaves that lay hidden between the reproduction of an ancient pre-columbine text, the rammed earth of the pedestal on which it stands, the warm ochre color on the walls, and the images of magnolia trees hidden by the interrupted carved line drawings of the woody plants are all part of the same narrative, earthly compounds that through mixture can radically transform the world. The exhibition is the result of an immersive process that recognizes marginalized knowledge as fundamentally deconstructed and nature as a universal, politically laden, and unifying force. By understanding the spectator as a geologic and living matter, Lorena Mal offers a stage to contemplate the landscape through active spectatorship and the

Árboles genealógicos (América: Magnolia)

2022

Dibujo calado sobre madera (frente) y fotografía del lugar de entierro de personas esclavizadas en la Plantación Latta Reserva Natural, Carolina del Norte (fondo)

244 x122 cm (frente) 343 x 365 cm (fondo)

Árboles genealógicos (América: Magnolia)

2022

Dibujo calado sobre madera (frente) y fotografía mural del lugar de entierro de los abuelos de Felipe, casa de Coyoacán en Ciudad de México (fondo)

244 x122 cm (frente) 243 x 91.44 cm (fondo)

Presencia Lúcida

Espacio de Arte Contemporáneo (ESPAC), Ciudad de México, MX

2019

Curaduría por Ana Torres Valle Pons