Biblioteca Terrestre (Cantera Tlayúa)

2025

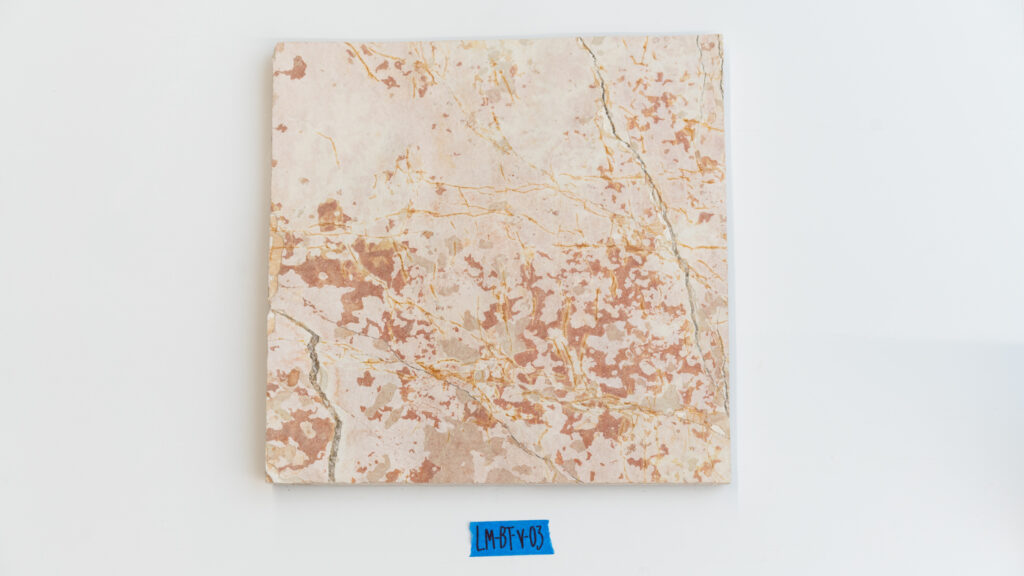

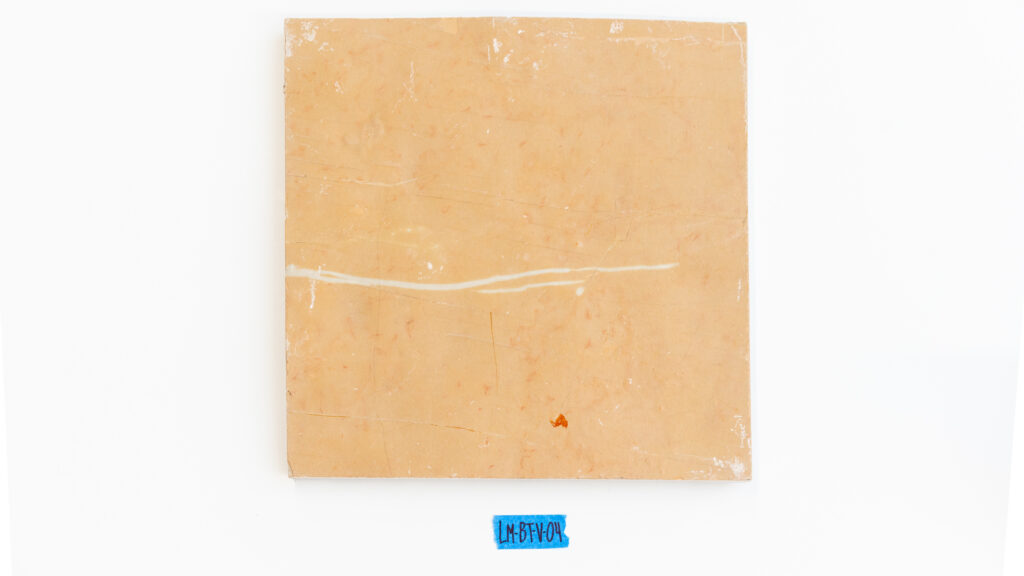

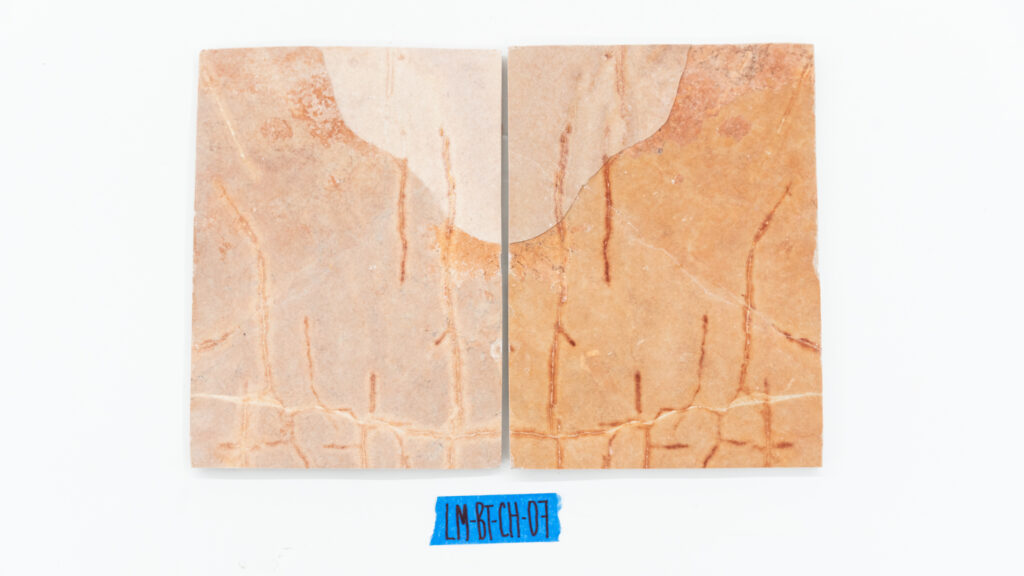

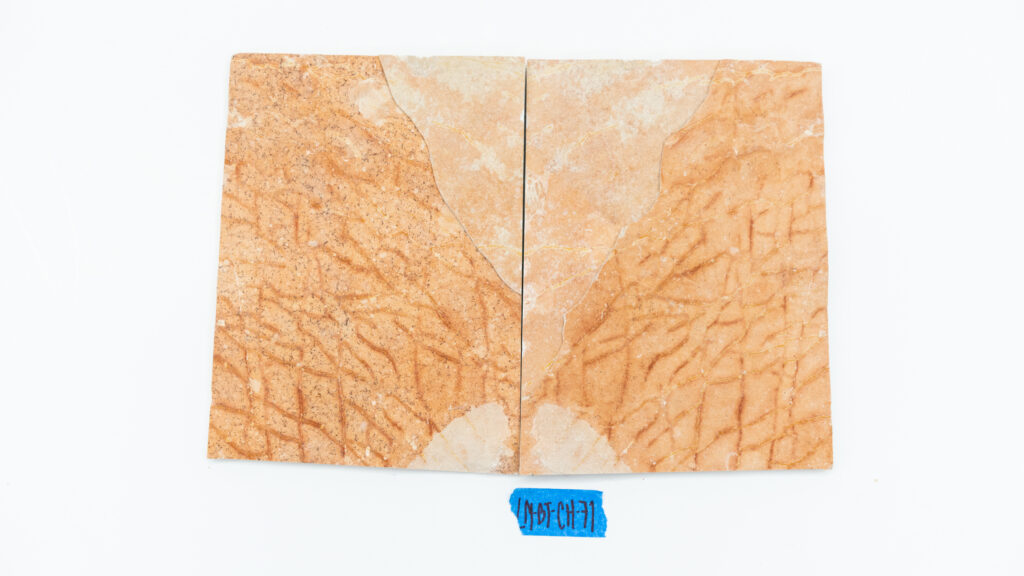

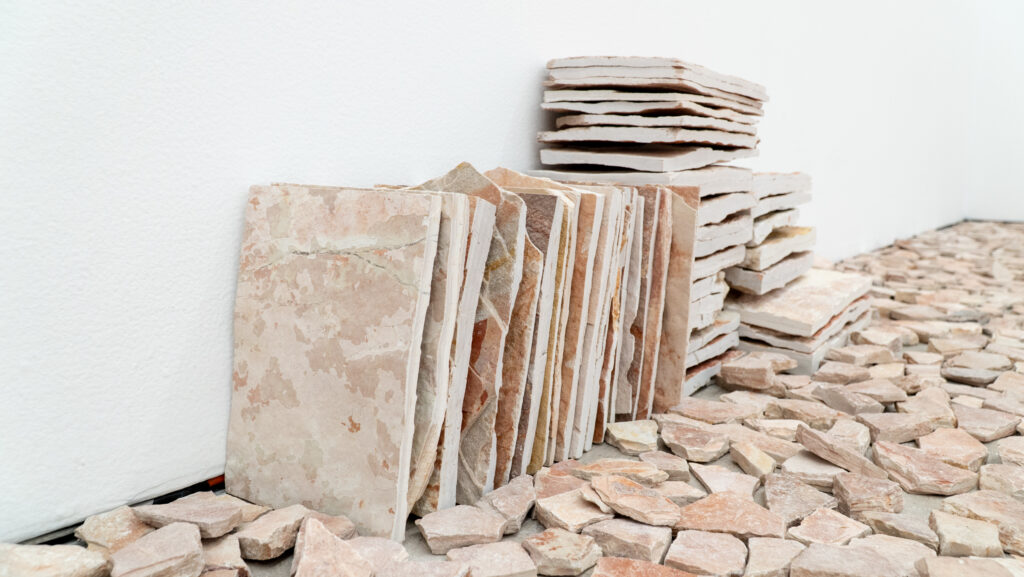

Instalación con piedra de 100 millones de años

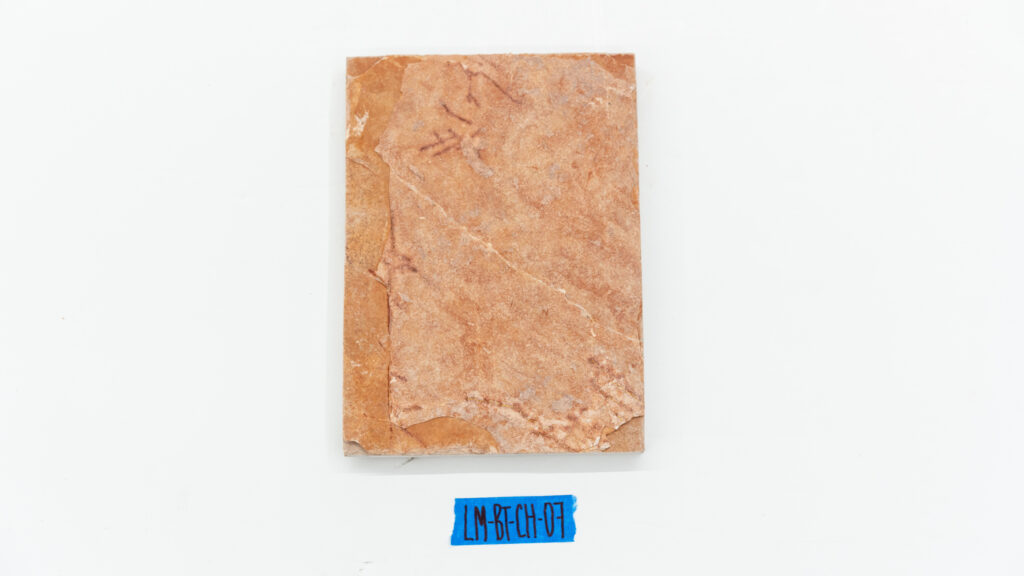

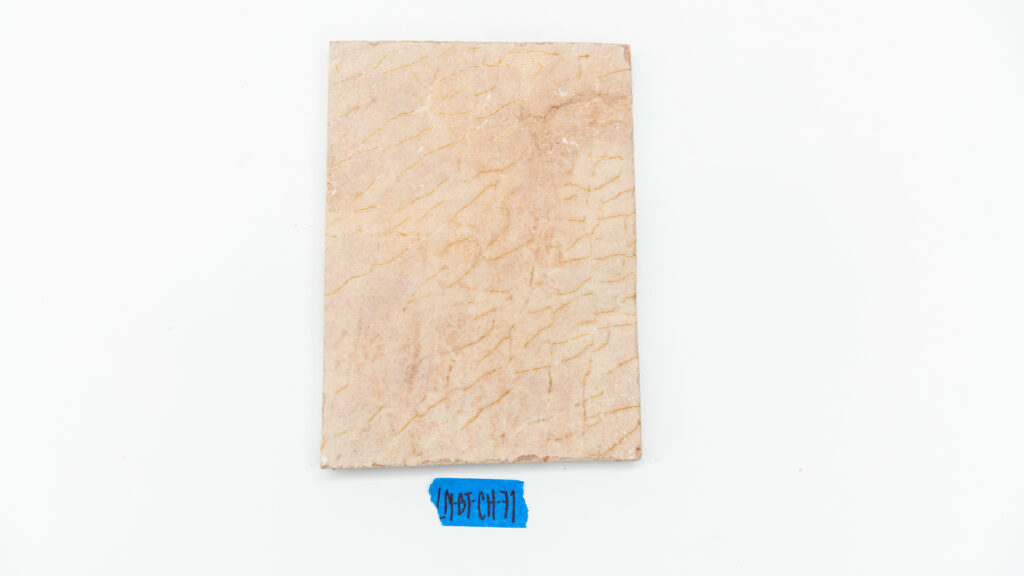

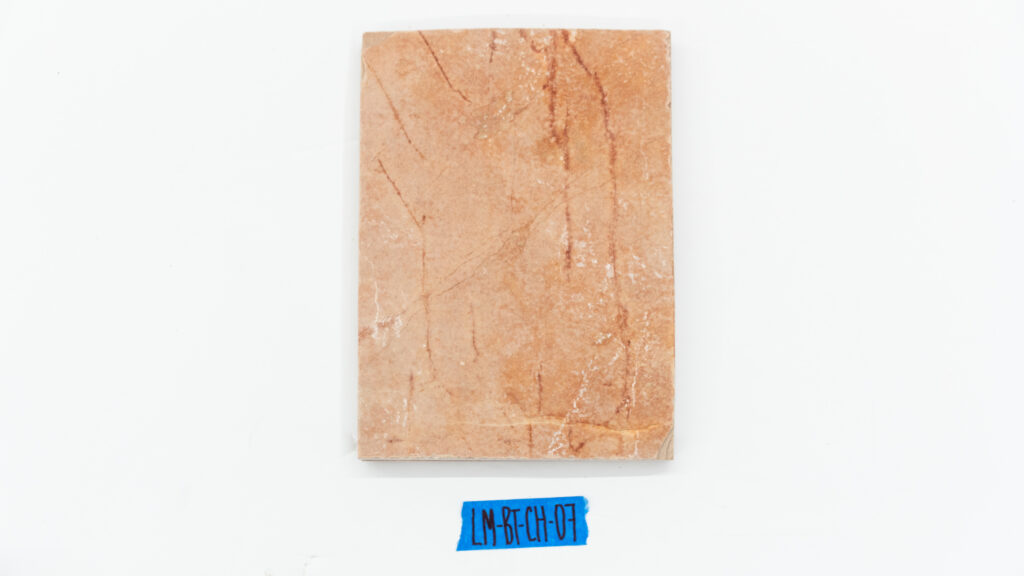

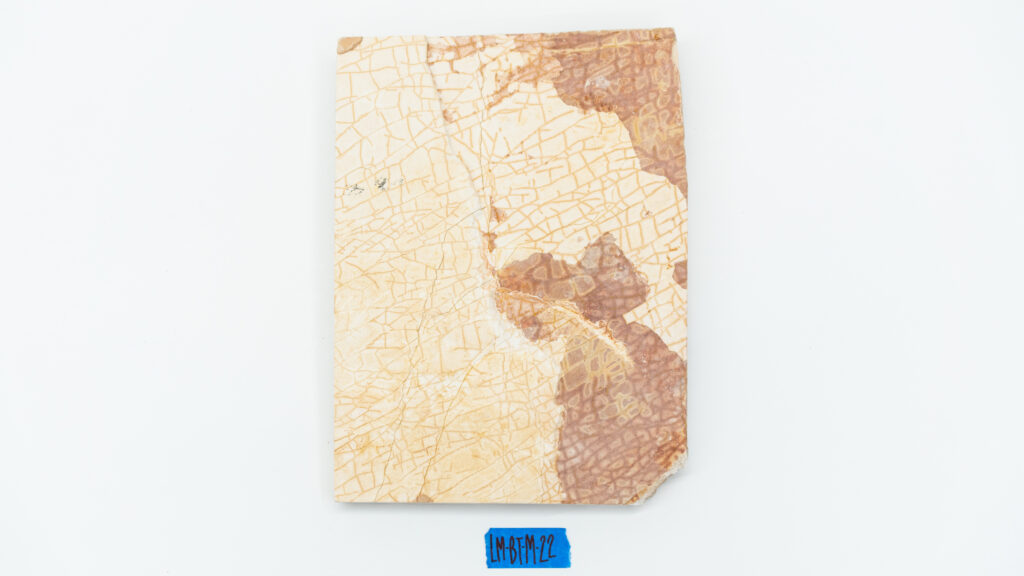

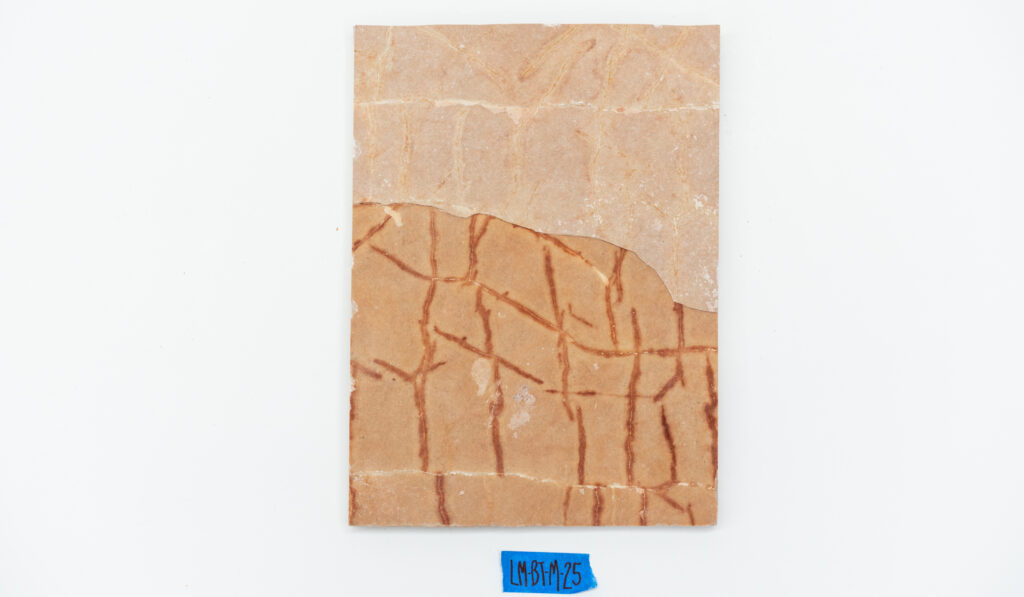

77 libros fósiles de bolsillo, 21x15cm

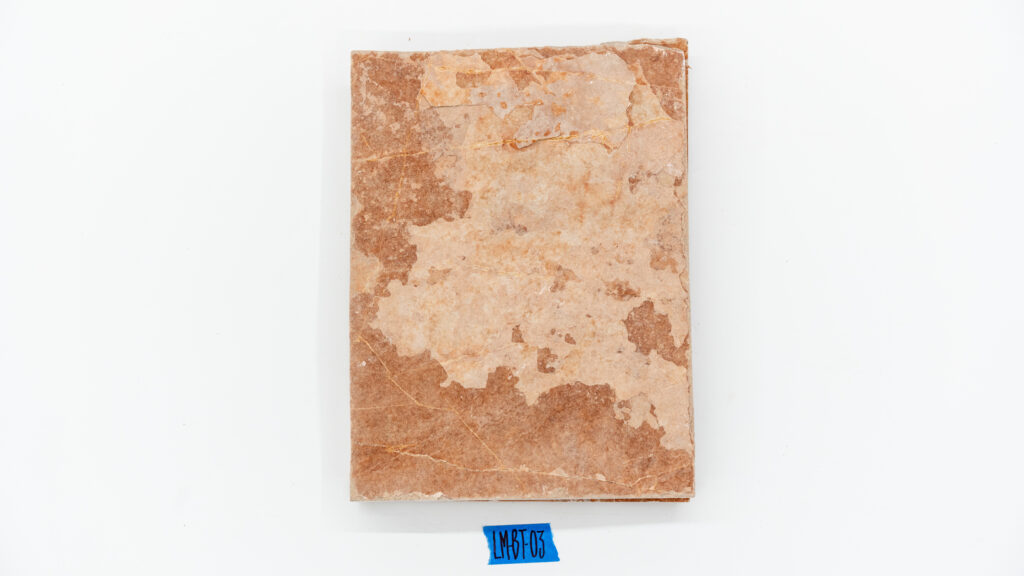

54 libros fósiles monográficos y revistas, 28x21cm

18 viniles fósiles, 31.5×31.5

y piso con fragmentos en área de 5x4m

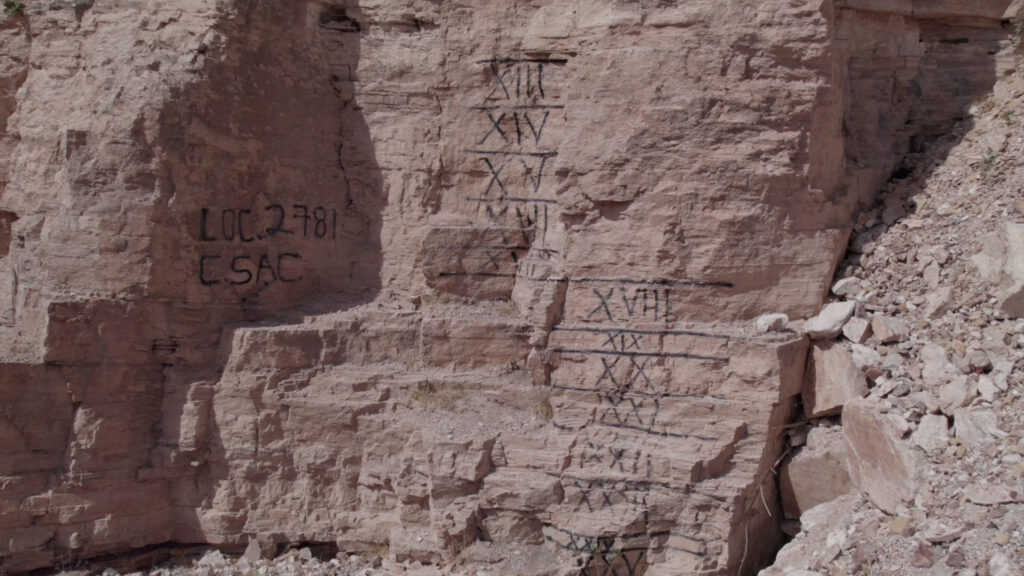

Montaje terrestre

2024-2025

Video 2K sin sonido

1′ (loop)

Concepto, dirección, producción y edición: Lorena Mal

Fotografía: Santiago Torres

Color: Ollin Miranda

Coordinación de producción: Ollin Miranda

Producción de línea (Tepexi de Rodríguez): Karmina Aranguthy

Producción nacional de artes visuales realizada con el estímulo fiscal del artículo 190 de la LISR (EFIARTES).

Proyecto realizado con el apoyo de Fundación Jumex Arte Contemporáneo.

Proyecto realizado con apoyo del Sistema de Apoyos a la Creación y Proyectos Culturales

Investigación en colaboración con Jesús Alvarado, Marisol Montellano-Ballesteros, Sergio Cevallos (Instituto de Geología, UNAM) y Francisco Regalado (LAAA).

En este proyecto participaron:

Felix Aranguthy

Karmina Aranguthy

Juan Carlos Aranguthy Castillo Faustino Aranguthy

Ranulfo Aranguthy Contreras Liliana Aranguthy Cabrera Sebastián Aranguthy Contreras Fátima Aranguthy

Carina Aranguthy Castillo Celina Aranguthy Castillo Jovani Joshua Aranguthy

Diana Palacios Aranguthy Allison Yoali Zavaleta Aranguthy Camila Aranguthy

Lizeth Aranguthy Castillo

Leticia Ruiz

Luz Aranguthy

Zayuri Aranguthy Lezama Fernando Aranguthy Castillo Elan Aranguthy Anaya

María Aranguthy

Alejandra Castillo Solís

Isa Aranguthy Castillo

Monserrath Tobon Aranguthy Katia Ramos Aranguthy Marisol García Ortega Nelson Aranguthy Cabrera Eliot Aranguthy Castillo Jesús Lezama Ojeda

Adrían Muñoz Merino José Luis Anaya Mario García Merino Abimael Martínez (dueño de la cantera) Marcelino Cruz Luna Emmanuel Martínez Cristian Martínez

En memoria de Magdalena Cabrera López

BIBLIOTECA TERRESTRE. FRACTURA SONORA.

Galería Arroniz

2025

Curaduría por Anna Dusi

Conversación con Anna Dusi y Lucía Hinojosa (fragmento)

[Anna Dusi]

Thank you to be here. I’m so happy and honored to… you know, invite you to this journey together. I thought to create this conversation because it’s important to have this in our tone.

Creating also an engagement through the audience, that it’s very important for me, and also the effect of how people react. Asking questions to you makes more sense for people —to feel emotionally, but also concentrate on very particular details of your practice— which is the most important thing on my part as a curator, but also as a person walking through your pace.

I thought to reflect and explore together this interdisciplinary journey with you, Lorena and Lucía, and so we want to interpret the surrounding space giving corporality to our voices and stories.

When I thought of the title Sound Fracture, I thought of change, the vibrant rupture of each body but above all, of the anthropological process of you, Lorena, and you, Lucía. So I’m asking the first question to Lorena —about your work, the reaction of the material, of memory and historical transformation. I would like to understand your process on this. I don’t know performative or performance but more related research.

[Lorena Mal]

Gracias, Anna. I really love how you point out a performative approach with also a process which comes with the research of my work. I think that all of my work comes from an environmental principle —which is to think how we are affected by the things that surround us, not only who we are, but also what we are, as something that we share with things as well, like human and more-than-human. We are all in a flux of transformations in time that are biological, but also chemical, geological, and that also involve a kind of metabolism of our own and of others.

For me, memory has to do with how we allow ourselves to be affected by what surrounds us. The human way in which we build into that memory. I find those same traces in materials, inscribed as footprints or scars. Materials sometimes resonate differently. So you can understand where they come from and how they came together, but from different perspectives.

In a way, sound is the same: we have these different kinds of pronunciations depending on where things come from. This relationship with materiality —which is also a relationship with stories and imagination and transformations in time— helps understand materials from a performative act. The behavior and dynamics that make them possible.

This also puts into question the notion of history, in terms of writing: what gets written, what gets preserved. Writing is situated, and there are a lot of forces implicated, which are political and a process of resistance —resistance in front of loss or forgetting, but also of oppression.

So for me, I try to establish different experiences with the world and with these conflicts. With this project, an earth library, a biblioteca terrestre: it is to look at landscape and think about the archive —how a landscape can also have a memory that is twisted, has directions, that implies a physicality resembling the idea of the book, and how we read through time, through its fragments and impulses of past times.

(…)

[Anna Dusi]

Thank you for your beautiful answer. To go back with you, Lorena —thinking about your specific piece and also your research focused on territory and environmental events that resonate with human existence— can you explain with more details this place that you create here and around it?

[Lorena Mal]

I think it has so much force to understand existence in itself as an environmental event, as you said, that involves us all the time, whether we understand it or not.

Part of my process these years has been to relate to different kinds of territories. The word territory itself has a lot of weight —it’s used to exploit or give away land, but also to defend it, approaching different territories. It is necessary to understand how land is distributed and exploited by humans, but also what it’s needed to defend these spaces that become part of us.

I’ve been establishing relationships with certain landscapes, tracing networks of connection —not of borders, but of links that sometimes happen beneath the earth. I think this is also a political practice, a form of reply that has to do with making roots into different worlds as well as our own past.

And in this case. There is this question: What do I have to do with this stone? What do I have to do with this mountain located in Puebla? This mountain formation —millions of years old, once under the sea towards Oaxaca—. The Tlayúa quarry tells a story of massive extinction recorded in the stone. For me, bringing this archive into this space is also bringing those stories and images, these “pocketbooks” these “petrified vinil records” that are there for us to listen and read.

How we think about writing has to do with multiplicity of existence and coexistence —more-than-human coexistence— and how putting attention to our own past and actions also means facing the destruction we’ve caused.

[Anna Dusi]

I feel very related to this concept, because it’s full of layers. There is so much that takes place —you recognize, but also identify things we can’t always see if we don’t have these resources. It’s beautiful how you think through the specific place, starting from a point to have a large view.

So, back to Lucía —this question of the rediscovered object related to your body of work. Do you think this reflection has an influence on your artistic practice? How?

[Lucía Hinojosa]

I love this question because it can go many ways. Relating to this conversation, I think we are, as a species —as mind, spirit, and body— related to all forms of forgetting. Forgetting is something we inherit along with memory, and there’s power and responsibility in understanding that.

My practice deals with time and how we are inhabited by this accumulation of life and death. Our minds are inscribed in this temporality of speech and process, just like nature.

Human language is how we’ve been taught to perceive ourselves in the narrative of the world, but I try to move away from that —to return to sound, to pure sound. Verbs and narration fragment our consciousness of the present. I come back to poetic language because it’s like an electric circuit —a high-voltage form of language.

Rediscovering the object means rediscovering that power, that sense of waking up in time and matter. Poetry, then, is more of an instrument —a system that allows us to inhabit the world differently, away from oppressive orders, rediscovering again and again that instance of dissolution.

(…)